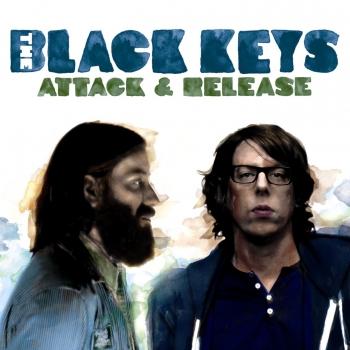

Attack & Release (Remastered) The Black Keys

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

2008

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

01.01.2021

Das Album enthält Albumcover

Entschuldigen Sie bitte!

Sehr geehrter HIGHRESAUDIO Besucher,

leider kann das Album zurzeit aufgrund von Länder- und Lizenzbeschränkungen nicht gekauft werden oder uns liegt der offizielle Veröffentlichungstermin für Ihr Land noch nicht vor. Wir aktualisieren unsere Veröffentlichungstermine ein- bis zweimal die Woche. Bitte schauen Sie ab und zu mal wieder rein.

Wir empfehlen Ihnen das Album auf Ihre Merkliste zu setzen.

Wir bedanken uns für Ihr Verständnis und Ihre Geduld.

Ihr, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 All You Ever Wanted 02:55

- 2 I Got Mine 03:59

- 3 Strange Times 03:10

- 4 Psychotic Girl 04:10

- 5 Lies 03:59

- 6 Remember When (Side A) 03:21

- 7 Remember When (Side B) 02:10

- 8 Same Old Thing 03:10

- 9 So He Won't Break 04:14

- 10 Oceans & Streams 03:26

- 11 Things Ain't Like They Used to Be 04:34

Info zu Attack & Release (Remastered)

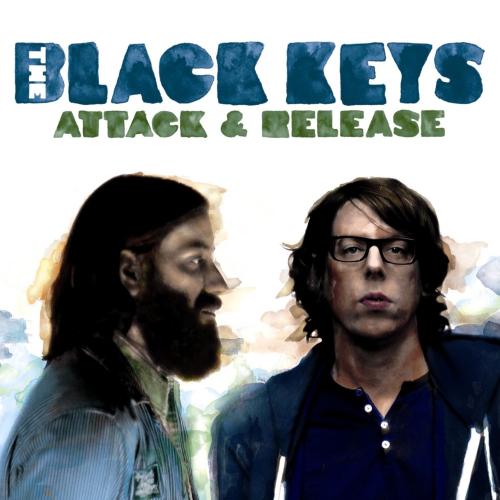

The Black Keys’ fifth full-length LP, Attack & Release, follows their 2006 critically acclaimed Nonesuch debut Magic Potion, which the Chicago Tribune proclaimed, “a gritty, wild, minimalist masterpiece.” Produced by Danger Mouse (Gnarls Barkley, The Gorillaz, The Grey Album), Attack & Release was recorded at engineer Paul Hamann’s illustrious Suma Studio outside Cleveland, Ohio. Initial collaboration began when Danger Mouse (a. k.a. Brian Burton) approached the band to write songs for an album he was developing with the late R&B legend Ike Turner. As the band began composing tracks for Turner early last year, though, they quickly realized they were actually laying the groundwork for a new album of their own.

Attack & Release thus became The Black Keys’ first collaborative effort, as it morphed into their own album with Danger Mouse as producer. By recording in an actual studio (another first), guitarist-vocalist Dan Auerbach and drummer Patrick Carney were given the opportunity to add a variety of instruments to their usual simple set-up—including organ, moog, and banjo. “After recording our previous albums in a basement, we were ready to go somewhere else,” Auerbach confesses. “Danger Mouse came in as our collaborator. He has a real ear for melody and arrangement and that was a big part of this record, as was the studio…a really special place.” Carney concurs: “The place is covered with dust, it smells like a moldy cabin, and it looks like a haunted house. It was fitting for our first time going into a real studio.” He continues, “I think Dan and I were intrigued to work with somebody as a producer, and with an engineer like Paul, because we both realized we couldn’t teach ourselves anything more and it was best to start learning from other people.”

Besides Auerbach, Carney, and Danger Mouse’s work, other contributions on Attack & Release include guitarist Marc Ribot and multi-instrumentalist Ralph Carney (Patrick’s uncle)—both veterans of, among other things, Tom Waits’ band. The closing track, “Things Ain’t Like They Used To Be,” features Auerbach singing along side eighteen-year-old bluegrass / country-singer Jessica Lea Mayfield.

The Black Keys have released four albums prior to Attack & Release––2002’s The Big Come Up, 2003’s Thickfreakness, 2004’s Rubber Factory, and 2006’s Magic Potion.

"Back in 2002, it seemed easy to discern which of the Midwestern minimalist blues-rock duos was which: the White Stripes were the art-punks, naming albums after Dutch art movements, while the Black Keys were the nasty primitives, bashing out thrilling, raw records like their 2002 debut The Big Come Up and its 2003 follow-up Thickfreakness. Six years later, the duos appear to have switched camps, as Jack White leads the Stripes down a path of obstinate traditionalism while the Black Keys get out, way out, on their fifth album, Attack & Release. Evidently, their 2004 mini-masterpiece Rubber Factory represented the crest of their brutal blues wave, as ever since singer/guitarist Dan Auerbach and drummer Patrick Carney have receded from the gnarled precision of their writing and the big, brutal blues thump, they started to float into the atmosphere with their 2006 EP-length tribute to Junior Kimbrough, Chulahoma. Ever since then, the Black Keys have emphasized waves of sound over either ballast or song, something that should be evident from the choice of Danger Mouse as the producer of Attack & Release, a seemingly unlikely pair that found common ground in the form of Ike Turner. Danger Mouse worked with the rock & roll renegade when he produced the Gorillaz's Demon Days and the plan was to have the Black Keys cut an album with Ike but Turner's death turned the project into a full-fledged Keys album. That's the official story, anyway, but the timeline doesn't quite seem to fit -- Ike died December 12, 2007 and a finished copy of Attack & Release was out in February, which is an awfully short turnaround to complete an album -- nor does the sound of the album seem to fit that timeline, either, as it's elliptical, open-ended, and reliant on the spacy sonics the Black Keys have sketched out since Rubber Factory, so it's hard to imagine where Turner would have fit into this. But it's not hard at all to see how avant guitarist Marc Ribot fits into this elastic mix, as this is the kind of restless, textural roots-aware rock reminiscent of the spirit, if not quite the sound, of Elvis Costello and Tom Waits, two mavericks Ribot has played with in years past. This shift to sound over song has been so gradual for the Black Keys that Ribot's cameo doesn't seem intrusive, nor does Danger Mouse's hazy production feel forced upon the band, it's filled with details so sly they're almost imperceptible. As always, Danger Mouse encourages the band to intensify what's already there, and so Attack & Release willfully drifts, as dreamy, artfully sonic sculptures are punctured by Auerbach's rumbling guitars and Carney's clattering drums. But where the interplay of the Auerbach and Carney always felt immediate in their earliest work, there's a bit of a remove here, with the riffs used as paint brushes instead of blunt objects. The same can be said of the songs, where even the most immediate tunes -- "Psychotic Girl," the B-side "Remember When" -- don't grab and hold like those on the group's earliest records, and they're not really growers either, as the point here is not the individual tunes but rather the greater picture, as everything here weaves together to create a mood: one that shifts but doesn't stray, one that's nebulous but not formless, one that's evocative but not haunting. To be sure, it's an accomplishment and one that showcases the Black Keys' deepening skills but at times it's hard not to miss how the duo used to grab a listener by the neck and not let go." (Stephen Thomas Erlewine, AMG)

The Black Keys

Digitally remastered

„Bis vor etwa drei Jahren hätte ich mir niemals vorstellen können, dass wir jemals 2.000 Tickets für eine einzige Show verkaufen würden“, lacht Black Keys-Drummer Patrick Carney. „Und jetzt spielen wir ununterbrochen in Hallen, die das Drei- bis Fünffache fassen.“ Ja: Der überragende Erfolg der Black Keys, der sich fast ein ganzes Jahrzehnt lang ankündigte und sich mit ihrem bislang letzten, sechsten Album „Brothers“ sensationell Bahn brach, überrascht niemanden mehr als die beiden Protagonisten selber.

Nicht nur, dass sie niemals damit gerechnet hätten, dass ihr schmutzstarrender Bastard aus Blues, Country, Boogie, Soul und Rock einmal zum Soundtrack eines kulturellen Zeitgeists werden könnte; Carney und sein kongenialer Partner, Sänger/Gitarrist Dan Auerbach, haben streng genommen viel dafür getan, dass es niemals so weit kommt. Ob Klang-Ästhetik, öffentliches Auftreten, visuelle Darstellung oder Produktions-Techniken: In bald jedem Detail dieser vielleicht besten aller Zwei-Mann-Combos steckt eine überzeugte Antihaltung gegenüber allem, was hip und gerade angesagt ist. Gerade darin liegt aber das Geheimnis ihres Erfolges.

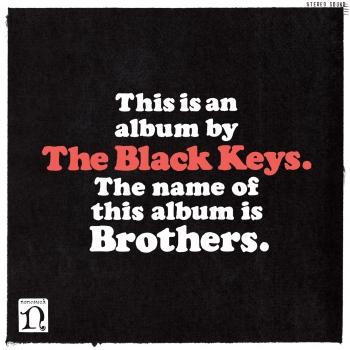

Die Cover-Gestaltung ihres letzten Albums spricht diesbezüglich Bände: In Anlehnung an ein (für die beiden sehr bedeutendes) Album der Blues-Legende Howlin’ Wolf prangt darauf lediglich die Ankündigung „This is an Album by The Black Keys. The name of the album is Brothers“. Weniger geht nicht, und trotzdem oder gerade deshalb gewannen sie für das Artwork einen Grammy – wie auch jene für das ‚Best Alternative Music Album’ und die ‚Best Rock Performance’. Spätestens seit diesem Award-Regen Anfang 2011 hat die Welt verstanden, dass die Black Keys mit ihrem herrlich bruddeligen Dagegensein den Nerv einer ganzen Generation treffen. Unnötig zu erwähnen, dass die beiden den Abend ihres bislang größten Triumphes nach 15 Minuten wieder verließen – ihnen war die Veranstaltung schlicht zu langweilig.

Ihr hohes Tempo sowie die Kunst, große Songs aus einer kleinen, simplen Idee zu entwickeln – das sind die beiden hervorstechenden Merkmale der beiden Nachbars-Kinder aus Akron/Ohio, die sich seit dem Sandkasten kennen, 1997 begannen, zusammen Musik zu machen, ihrem gemeinsamen Treiben aber erst 2001 den Namen Black Keys gaben. Ihr erstes Angebot für einen Deal mit einem Major-Label schlugen sie aus, weil ihnen die zweiwöchige Frist bis zum Aufsetzen des Vertrags als zu lang erschien; kein Wunder bei einer Band, die in der Vergangenheit schon komplette Alben in einer einzigen 14-stündigen Session einprügelte. Gerade diese Ungeduld und sprühende Hitze des Moments ist es, was die Musik der Black Keys auszeichnet und in einer Welt voller generalstabsmäßigen Karrieren so kurios und mitreißend anmutet.

Und doch ist ihr Erfolg weder Glück noch Zufall. Wie nur wenige Bands der gegenwärtigen Rockszene haben die Black Keys die ganz brutale Ochsentour absolviert, sind über Jahre in einem altersschwachen Van durch die Staaten getourt und haben in Clubs auf dem Boden geschlafen. Bis 2006 galten sie höchstens als strenger Geheimtipp für Fans eines authentischen, obschon modernisierten Blues-Feelings. Bis dahin hatten sie bereits vier Alben veröffentlicht.

Doch dann passierte ihnen Danger Mouse alias Brian Burton. Der Mann hinter Gnarls Barkley und Produzent der Gorillaz betreute ein Projekt namens Blackroc, bei dem sich die beiden Sound-Nerds mit dem großen Faible für Vintage-Instrumente in einen kreativen Clinch mit HipHop-MCs wie Mos Def, RZA, Raekwon, Q-Tip oder Pharoahe Monch begaben. In Danger Mouse fand das Paar, das sich bis dahin stoisch gegen jede Einflussnahme von außen geweigert hatte, den perfekten Produzenten jenseits aller Rock-Klischees – und ihr fehlendes drittes Glied für die Studio-Arbeit. Zur selben Zeit reüssierten Carney und Auerbach überdies mit Einzelgängen: Der Frontmann nahm ein Solo-Album auf, der Schlagzeuger veröffentlichte ein Album seines Percussion-Projektes Drummer.

Derart gerüstet, brach mit der Aufnahme ihres nächsten Albums „Brothers“ eine neue Zeitrechnung an: Der Blues wurde aufgebrochen und um noisige, soulige und swingende Elemente ergänzt. Den satten Groove hatte man sich bei der Blackroc-Arbeit abgeschaut. Und mit Danger Mouse saß nun erstmals ein Produzent mit im Studio, der ihre Vorstellung eines betont unmodischen, kantig erdigen und trotzdem homogenen Sounds teilte. „Wir wollen, dass unsere Platten richtig scheiße klingen. Aber das bitte gut“, ist ein legendäres Zitat von Dan Auerbach zu ihrer Sound-Ästhetik.

Der Rest ist Geschichte. „Brothers“ wie auch die Single-Auskopplung „Tighten Up“ markieren den finalen Durchbruch der Black Keys. Beide Veröffentlichungen notierten weltweit in den Top Ten. Alle wichtigen Fachorgane wie Rolling Stone, Spin, Time, Uncut, Mojo oder Q platzierten „Brothers“ in ihren ‚Alben des Jahres’-Listen ganz oben. Allein in den Nordamerika verkaufte es sich über 900.000 Mal, die Tour zum Album war zu hundert Prozent ausverkauft.

Und nun also: „El Camino“, Album Nummer sieben und ihre nunmehr dritte Zusammenarbeit mit Danger Mouse. Entstanden im zwar neu gebauten, aber fast ausschließlich mit Uralt-Equipment bestückten Band-eigegen ‚Easy Eye Sound System’-Studio in Nashville, markiert auch dieses Werk einen Neustart. Die Black Keys haben sich mit den Anforderungen an ihren gewaltigen Erfolg arrangiert und ihren wunderbar kompromisslosen Kellersound behutsam aufgehübscht; sie haben hyperventilierende Blues- und Boogie-Songs geschrieben, die sofort in die Beine gehen, und sie mit Melodien versehen, die man nach nur einem Hören des Rest des Tages vor sich hin summt. Damit ist ihnen geglückt, wonach die meisten Bands verzweifelt suchen: Die Formel für perfekte Songs, für das knackigste Elf-Song-Album, das denkbar ist, und eine atemberaubende Balance zwischen kauzigem Subkultur-Sound und breit aufgestellter Hit-Tauglichkeit.

Dieses Album enthält kein Booklet