A German cellist and a Russian pianist have joined up exclusively for this album to record works by Russian composers, which were created during the transition from the nineteenth to the twentieth century through the thirties. Both belong to the younger generation of musicians with 37 and 30 years, and each can already look back on an impressive international career. The cellist Johannes Moser, who holds a professorship at the Cologne University of Music and Dance, comes from a musician family whose well-known members include his mother, soprano Edith Wiens and his aunt, soprano Edda Moser. The eight-year-younger Andrei Korobeinikov has been committed to playing the pianoforte since he was five years old, and just three years later he began to earn a competition prize after another. Somehow, he must have mastered the Wunderkind-like meteoric ascent, without being broken thereby like many of his competitors. Anyhow he is actively participating in the international concert scene as a soloist as well as a chamber musician and as a chamber musician, as does his cello-playing duo partner.

Rachmaninov and Prokofiev mark contrary positions in the Russian music scene of their time: while Rachmaninov imported the romantic approach of the nineteenth century into the twentieth century and carefully subordinated this approach to a more modern sound design, the twenty-years-younger Prokofiev soon left the romantic approach behind and found instead quickly to a cool formalistic form of composing, which appears to us later born ones refreshing and sometimes soothingly bizarre. What connects both composers, apart from their Russian origin, is the virtuosic mastery of the piano in the succession of a Franz Liszt. Sound recordings tell of this common heritage as well as the treatment of the piano in the compositions collected on this album. What connects both composers and divides them is due to the existential pain caused by the older Rachmaninov’s leaving his home country at the time of the tsarist fall and living abroad henceforth, while Prokofiev, like so many of his countrymen suffered under the political situation, caused by his staying to his home country.

The contrasting musical worlds of Rachmaninov and Prokofiev are clearly reflected in the thoroughly convincing interpretation of their cello-piano sonatas by the two artists on this album, who act appropriately for the most part as equal partners and not as companion and escort, such as at the beginning of Prokofiev’s Sonata Op. 119, which in the middle part - typical of this composer – works off the existential pain through irony and in the finale by non-romantic seriousness intoned by the pianist and the cellist in the way of a large-scale orchestra. On the other hand, the existential pain propagates in Rachmaninov’s Sonata Op. 19 by Rachmaninov after a short introduction in the first movement, wrapped in an elegant, multi-faceted melodic stream, like the third piano concerto, to be spun across in the second movement shrouded in velvet darkness, and after violent major and minor changes in the third movement opening into an overwhelmingly towered finale to which the painful light flashes repeatedly.

The fact that the third member of the composers represented on this album, Alexander Scriabin, who is viewed by some music lovers as standing out like a bird of paradise of the mass of Russian composers, is not mentioned on the cover, seems a little strange, especially since his Romance for cello and piano - the cello-part was originally drafted for horn - perfectly fits into the romantic surroundings of Rachmaninov, and is as affectionately taken charge of by the two artists as the compositions of Rachmaninov and Prokofiev. Perhaps it was the extremely short duration of the romance of just two minutes, which motivated the cover designers to drop Scriabin as a third composer. If this were the case, those designers should bear in mind that the value of a work should be measured not by its length, but by its content, which, in the case of Scriabin's romance, is not lower than the content of the three times longer Vocalise of Rachmaninov thanks to the creativity of the duo Moser & Korobeinikov.

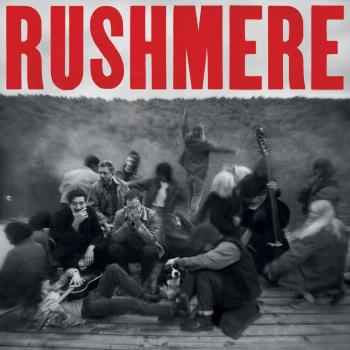

Apart from the faux pas, not to mention Scriabin on the cover, the small birch forest depicted thereon, rich in associations, takes us to Russia. Why, however, Johannes Moser, uncomfortably resting on the forest floor, crouching on the Andrei Korobeinikov seated there with astonishment, does not fit either to the small birch forest or to the Russian mood of the album’s content, but rather to the current tendency to make covers compulsively casual. It doesn’t really mind with an album of the highest musical quality, technically finding its equivalent ever since considered “bon ton” by Pentatone in the strict term of the sense.

Johannes Moser, cello

Andrei Korobeinikov, piano