Schubert [arr. Mahler]: Death and the Maiden / Shostakovich [orch. Barshai]: Chamber Symphony in C Minor

The crashing triplets of the first ten bars of the D minor death dance, originally composed as a quartet, drive out of the loudspeakers like a lightning bolt out of the blue. As in Beethoven's destiny symphony, this theme dominates the first quartet. But it is not the death which is bitter for Schubert, but life, his life: "... I feel myself to be the most unfortunate, miserable man in the world. Think of a man whose health is never going to be right, and who, out of despair, makes the matter worse and worse, think of a man, I say, whose most brilliant hopes have been ruined, whom the happiness of love and friendship offer nothing but pain, at the most, whom enthusiasm (at least stimulating one) threatens to fade for beauty, and I ask you whether that is not a miserable unhappy man? ‘My rest is gone, my heart is heavy, I never find it, ever,’ I can now sing every day, for every night when I go to sleep, I hope no more to wake; and every morning only tells me yesterday’s grief. So joyful and friendless I spend my days ... ".

How differently touching and frightening the introductory measures of the first movement, and thus Schubert's deep soul-suffering can be realized, one has learned from the numerous interpretations of different quartet formations. Through the introductory measures in Mahler's string saturated adaptation in the interpretation of Roman Simovic conducting 28 strings of the LSO whose young concertmaster he is in addition to pursuing a solo career, a veritable thunderstorm catches the audience which cannot be picked by the smaller quartet for lack of man power. The string saturated orchestration demonstrates in the further course of The Death and the Maiden that the larger cast is not only able to produce a strong effect, but can also portray delicate passages just as impressively, thereby rejecting the contemporary critics of Mahler posthumously that the larger casting would not be able to produce intimate intensity. At any rate, Mahler was so discouraged by this criticism that he merely completed his work on the quartet’ first movement. The rest of the movements were arranged in the 1980s by the musicologist Donald Mitchell and the composer David Matthews for large string sections, and were subsequently frequently performed and stored on recoding media. In April 2015, the live performance in the London Barbican Centre by Roman Simovic, who animated the LSO strings to an expressive playing and built up a convulsive intensity in delicate passages, takes a prominent position on recording media and downloads.

Also the second composition of this download, the Chamber Symphony in C Minor is an arrangement, more precisely an orchestration of the String Quartet No. 8 of Dimitri Shostakovich by Rudolf Barschai, who undertook the orchestration of the quartet at his time as chief conductor of the Moscow Chamber Orchestra; and he also successfully performed it with this orchestra. No less bleak than the Schubert Quartet the Chamber Symphony reflects the depressed mood of the composer, who had written the quartet, in which the composer's initials DSCH resoundingly play a roll, in just three days. The orchestration by Barschai was recognized by his friend and teacher Shostakovich as a valid version of the original work.

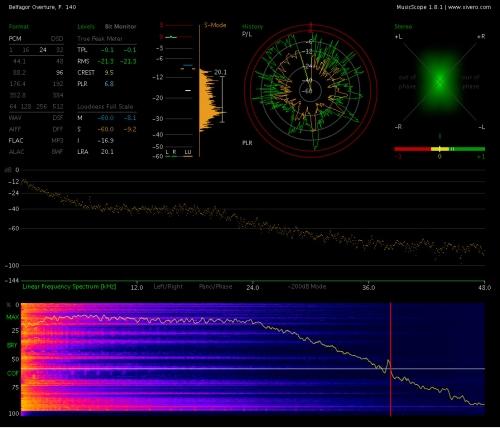

In addition to lyrical parts, which are masterfully made blossom and faded away by the LSO strings, Shostakovich promotes a structured bass, abruptly breaks, shrieking, grimaceous passages, which are full of striking impressions, even frightening in full string section: despair in Russian. Strong nerves are the prerequisite to be able to follow the crass performance of the composer's strongly attacked soul life without suffering damages. The recording technique neither brightens Schubert's despair nor the Shostakovian depression. In both cases, at best the legendary virtuosity of the LSO strings donates consolation.

London Symphony Orchestra String Ensemble

Roman Simovitch, conductor