Beethoven: Piano Soantas, Nos. 30, 31 & 32 Mari Kodama

Album info

Album-Release:

2012

HRA-Release:

30.08.2012

Label: PentaTone

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Concertos

Artist: Mari Kodama

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Album including Album cover

- Piano Sonata No. 30 in E, Op. 109

- 1 I. Vivace ma non troppo 03:22

- 2 II. Prestissimo 02:24

- 3 III. Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung: Andante molto cantabile ed espressivo 13:05

- Piano Sonata No. 31 in A flat, Op. 110

- 4 I. Moderato cantabile molto espressivo 06:24

- 5 II. Allegro molto 02:00

- 6 III. Adagio ma non troppo 03:38

- 7 III. Fuga: Allegro ma non troppo 06:28

- Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111

- 8 I. Maestoso: Allegro con brio ed appassionato 09:44

- 9 II. Arietta: Adagio molto semplice e cantabile 15:54

Info for Beethoven: Piano Soantas, Nos. 30, 31 & 32

Reviewing Beethoven sonatas is hazardous. Several ‘definitive’ recordings exist, most recently by Alfred Brendel; though experts disagree. Is it a matter of personnel taste or, may be, even of ‘make believe’? What makes a good interpretation? It is not easy to get a clear idea about the emotional roots of the sonatas. This may not be essential for Beethoven’s early sonatas, but, to my mind, increasingly so for the latter ones. Beethoven said: ‘I compose what I feel in my heart’. For all I have read about the life and works of Beethoven, there is so much controversy that it is still a mystery to me what really went on inside on any particular moment and what ‘vision’ moved him to compose a particular sonata.

One thing is certain: Beethoven has always been intrigued by young and beautiful women. This has clearly found reflection in several of his sonatas. For instance in Op. 27/2 ‘Moonlight’, and Op. 78 ‘For Therese’. But in his continuous strive for fame and recognition, especially amongst nobility, he also drew inspiration from a mixture of impatience, anger and disappointment. It would be interesting to know how Beethoven himself played his sonatas.

Remarks to that effect from his old friend Wegeler were not always flattering: too rough, too loud. He (Wegeler) once took him to the pianist Sterkel, whose playing was light, gentle and feminine; Beethoven stood by and immediately copied. Others, like Romberg and Czerny were impressed by his ingenuity and virtuosity, though agreed that his playing was more often fierce and savage. And as his hearing grew worse, his hammering on the keys got worse too, until he decided to no longer to play in public.

Another typical phenomenon is that Beethoven’s sonatas seem to be a man’s affair; complete cycles with women are rare. Annie Fischer’s cycle (Hungaroton) is fantastic, but the recorded sound is not optimal. The only new female cycle that I know of, is the one of the young Korean ‘U Tube’ piano acrobat, HJ Lim, to be issued shortly on EMI/RBCD. Does Mari Kodama stand a chance against stiff (male) competition and pre-conceived ideas about ‘Wunderkinder’ from the Far-East?

It is a known fact that the piano is amongst the most difficult instruments to record. Wide frequency spectrum and dynamics are demanding. If we take Arthur Schnabel, whose musical and emotional, yet very personal interpretation, seen by many as a landmark, as an example, we must sadly note that even in the best re-mastered CD form, it still sounds flat, tinny and, in the end, tiresome. Neither recording technicians nor the medium in those days were able to capture the full frequency band and the dynamics of a concert grand, thus losing much of the ‘real thing’. Other ‘definitive’ recordings (Backhaus, Kempff) suffer, albeit to a lesser degree, from poor sound, as well.

Kovachevich and certainly Brendel profit from modern recording techniques, much more able to convey the real picture. For some, these are ‘must have’ recordings, but I suspect that for RBCD limiters have been used to avoid distortion. (Not everyone is too concerned about that).

In this respect, jubilant reviews of Igor Tchetuev on Caro Mitis are revealing. The more so, because Tchetuev is not one of the current Big Names. Not only is this another example of the fact that there is more talent out there than the big label marketing teams want us to believe, but also that there seems to be another element contributing to his success: Reviewers refer to the recording quality, bringing the beauty of the Fazioli grand piano into one’s living room. It would seem, therefore, that sound quality can and, indeed, does play a pertinent role in an overall appreciation.

Back to Kodama.

Some time ago I bought, out of curiosity rather than conviction, Mari Kodama’s account of the sonatas 16, 17 (Tempest) and 19 (The Hunt). I was immediately struck by the impact of her playing and the ‘realism’ of the recording. As if I was sitting next to her. Here, too, we deal with the same Polyhymnia people, responsible for the Caro Mitis recordings. This confirms my view that sound quality does not only play an important role in the overall appreciation, but also that ‘dynamics’ are an integral part of conveying ‘emotion’.

As for her musical credentials: Kodama’s playing grows on you. I bought several more of her recordings and the more I listened the more I liked what I heard. She has an elegant and a sensitive, female touch, but does at the same time not shy away from the more powerful passages. She combines a male approach with bringing out gentle and sometimes hidden feminine intentions. Her musical ‘palette’ stretches from searching to assertive. She, furthermore, refrains from unwanted glamour by not turning everything into a speed contest. Her playing resembles that of Alfred Brendel. Not surprisingly so, because he was for some time her teacher and mentor (like Paul Lewis, by the way).

At this stage of the ongoing cycle, I do not think that anyone has any doubts about Mrs. Kodama’s virtuosity and technical abilities. Musically, the proof of the pudding may be these complex last three ‘end of career’ sonatas.

Beethoven’s style had shifted away from a more structural approach to a kind of ‘story telling’. (Beethoven has always been surprised that people did not ‘see’ anything but music when they were playing his sonatas). Hence, the interpreter’s capacity to convey a story seems just as important as playing the notes. Kodama does not disappoint. In doing so, her tempi are faster than Brendel (decca), but not as fast as Brautigam (BIS). May be due to her cultural, Japanese background, her playing remains delicate throughout, even in the louder passages, and I am glad that she didn’t fall for the trap in the syncopated variation in the second movement of the ultimate sonata no. 32, Op. 111, playing it too jazzy like Pogorelic in his younger years. She thereafter takes you by the hand to the end of the road where Beethoven’s final piano tones die out in resignation and eternal fame.

Does all this make here a preferred choice? For me, there are no ‘definitive’ recordings. It is hard to believe that since Schnabel cs. there have not been others who are at least equally competent; each one perhaps telling a slightly different story. I think that Beethoven’s sonatas are strong enough to accommodate several approaches. And Kodama’s is certainly one of them, with the added advantage of glorious and realistic piano sound.

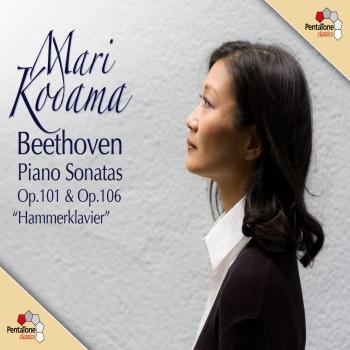

I, for one, look forward to the concluding issues of this cycle, with, among others, Beethoven’s best (his own words) and perhaps most difficult sonata no. 29 ‘Das Hammerklavier’. (Adrian Cue, France, May 7, 2012)

'This release is the latest addition to the complete Beethoven piano sonatas cycle by Kodama. Her previous releases in this series have been well received. “Never bearing down on heavily on the music, she always allows Beethoven his own voice.” (Gramophone)

Mari Kodama, piano

Mari Kodama - Piano

Mari Kodama has established an international reputation for profound musicality and articulate virtuosity at the keyboard. In performances throughout Europe, the United States and Japan, she plays a broad repertoire in a powerful yet elegant style.

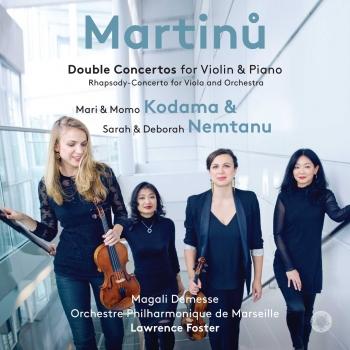

The 06/07 season begins with performances of the Mozart Double Piano Concerto in Japan with her sister, Momo Kodama, and a recital at the Roque d'Antheron Festival in France. In the U.S. this season, Ms. Kodama plays Beethoven Piano Concerto No.2 with the Philaharmonia Baroque in San Francisco, Beethoven Piano Concerto No.4 with David Stahl and the Charleston Symphony, and the Haydn Concerto with Mark Wigglesworth and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. This season also marks the end of her complete Beethoven sonata cycles in Tokyo and Nagoya, as well as the completion of her recording of all five Beethoven Piano concerti with Kent Nagano and the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin.

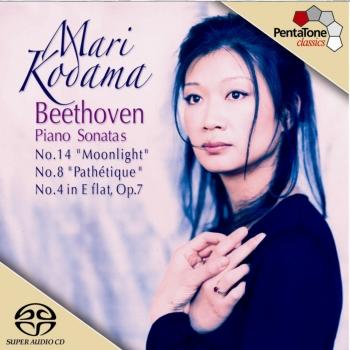

Recent highlights include Mozart concerti with the Gulbenkian Orchestra in Portugal as well as Beethoven concerto performances with orchestras in Montreal, Venezuela, Singapore, and Berlin. She played the Schoenberg Concerto with Jonathan Nott and the Bamberg Symphony, a work she has performed also with the American Symphony Orchestra, the Vienna Symphony, and on tour in the Netherlands. In Japan, Ms. Kodama is a regular guest with both the Tokyo Metropolitan Orchestra and the Yomiuri Nippon Orchestra in Tokyo. She played a surpassingly well-received complete Beethoven sonata cycle in Los Angeles, and has appeared in recital in New York, Paris, throughout Japan, Spain and Germany, and much of the U.S. The Los Angeles Times pronounced her performance of the Prokofiev Third Piano Concerto at the San Luis Obispo Mozart Festival 'commanding and electrifying.' Ms. Kodama has recorded Prokofiev concerti Nos. 1 and 3 with the Philharmonia Orchestra on the ASV label, and Chopin No. 2 and Carl Loewe's 2nd piano concerto with the Russian National Orchestra on PentaTone Classics. She is also featured on a new recording of Beethoven piano sonatas [PTC 5186-023]. This release, the second installment in her traversal of the complete Beethoven sonatas for the Dutch label, features the 'Moonlight' sonata, Sonata No.4, Op.7, and the 'Pathétique' sonata. The recording is Ms. Kodama's third for the Pentatone label.

Ms. Kodama is a founding member of chamber music festivals in San Francisco, Sapporo and Gmunden. The most unusual of these endeavors is Musical Days at Forest Hill, a set of four concerts presented by Ms. Kodama and her husband, conductor Kent Nagano, at their home in the Forest Hill section of San Francisco (insightcc.com/musicaldays). Rave responses prompted the return of the series in July 2006, with performances by artists including Ms. Kodama, her sister Momo Kodama, baritone Dietrich Henschel and composer-pianist Ichiro Nodaïra. In previous seasons Ms. Kodama has invited friends and colleagues from the Vienna Philharmonic, the Berlin Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, and prominent freelancers from France, Austria and the U.S. to play chamber music at the Forest Hill Club House as a gift to the community. Repertoire ranges from Bach to Messiaen to Schoenberg to Schumann to Schubert, with newer music by such composers as Jacob Druckman and Kurt Rohde.

Born in Osaka and raised in Paris, Ms. Kodama studied piano at the Conservatoire National in Paris with Germaine Mounier and chamber music with Genevieve Joy-Dutilleux. She has also worked with Tatiana Nikolaeva and Alfred Brendel.

Ms. Kodama has played with such orchestras as the Berlin Philharmonic, London Philharmonic, Philharmonia Orchestra, Hallé Orchestra, the Montreal Symphony, the North German Radio Orchestra, Vienna Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Berkeley Symphony, the American Symphony Orchestra, and the NHK Orchestra in Japan. She made her New York recital debut at Carnegie's Weill Recital Hall in 1995. Her U.S. festival appearances include Mostly Mozart, Bard Music Festival, the Hollywood Bowl, California's Midsummer Mozart Festival, Ravinia, and Aspen. In Europe she has appeared at festivals in Lockenhaus, Lyon, Montpelier, Salzburg, Aix-en-Provence, Aldeburgh, Verbier and Évian.

Kent Nagano - Conductor

Kent Nagano is renowned for interpretations of clarity, elegance and intelligence. He is equally at home in music of the classical, romantic and contemporary eras, introducing concert and opera audiences throughout the world to new and rediscovered music and offering fresh insights into established repertoire. In September 2006 he became Music Director of both the Bayerische Staatsoper and the Montreal Symphony Orchestra.

Born in California, Nagano maintains close connections with his home state and has been Music Director of the Berkeley Symphony Orchestra since 1978. His early professional years were spent in Boston, working in the opera house and as assistant conductor to Seiji Ozawa at the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He played a key role in the world premiere of Messiaen’s opera Saint François d’Assise at the request of the composer, who became a mentor and bequeathed his piano to the conductor. Nagano’s success in America led to European appointments: Music Director of the Opéra National de Lyon (1988-1998), Music Director of the Hallé Orchestra (1991-2000).

During Nagano’s first two seasons in Munich he conducted world premieres of Rihm’s Das Gehege (together with Strauss’s Salome) and Unsuk Chin’s Alice in Wonderlandalong with new productions of Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina, Idomeneo, Eugene Onegin and Ariadne auf Naxos. This season he takes on new productions of Wozzeck andLohengrin. He has toured throughout Europe with the Bayerisches Staatsorchester and their recording of Bruckner’s Symphony No 4 was released earlier this year by Sony Classical.

A common thread has thus far run through Nagano’s time in Montreal: Beethoven and his musical heirs including Mendelssohn, Brahms, Schumann and Wagner. Highlights have also included Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder and concert performances of Tannhäuser and Tristan und Isolde. In the summer of 2008 Nagano inaugurated the first Bel Canto Festival including performances of Bellini’s Norma in collaboration with Accademia Nazionale Santa Cecilia in Rome. He has also championed new works by Canadian composers including a commission by Alexina Louie which features Inuit throat singers and earlier this season celebrated Messiaen’s centennary with performances of St. François d’Assise. Nagano has taken the orchestra on a coast-to-coast tour of Canada and also to Japan and South Korea and in April 2009 an extensive tour of Europe. Their recordings together – Beethoven : Ideals of the French Revolution and Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde were released this year on Sony Classical / Analekta.

A new and important phase of Kent Nagano’s career opened when he became Artistic Director and Chief Conductor of the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin in 2000. He has become a prominent figure in a new wave of artistic thinking in Germany, opening minds to inventive, confrontational programming. In June 2006, at the end of his tenure with the orchestra, he was given the title Honorary Conductor by members of the orchestra, only the second recipient of this honour in their 60-year history.

Kent Nagano became the first Music Director of Los Angeles Opera in 2003 having already held the position of Principal Conductor for two years. His work in other opera houses has included Shostakovich’s The Nose (Deutsche Staatsoper Berlin), Rimsky Korsakov’s The Golden Cockerel (Châtelet, Paris), Saariaho’s L’amour de loin (Salzburg Festival), and Hindemith’s Cardillac (Opéra National de Paris).

As a much sought-after guest conductor he has worked with most of the world’s finest orchestras including the Vienna, Berlin and New York Philharmonic Orchestras and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He has recorded for Erato, Teldec, Pentatone and Deutsche Grammophon as well as Harmonia Mundi, winning Grammy awards for his recordings of Busoni’s Doktor Faust with Opéra National de Lyon, and Peter and the Wolf with the Russian National Orchestra.

This album contains no booklet.