Franck: Symphony in D Minor, FWV 48 (Remastered) Guido Cantelli

Album info

Album-Release:

2020

HRA-Release:

10.04.2020

Label: Warner Classics

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Artist: Guido Cantelli

Composer: César Franck (1822-1890)

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- César Franck (1822 - 1890):

- 1 Franck: Symphony in D Minor, FWV 48: I. Lento - Allegro non troppo 17:14

- 2 Franck: Symphony in D Minor, FWV 48: II. Allegretto 09:36

- 3 Franck: Symphony in D Minor, FWV 48: III. Allegro non troppo 09:39

Info for Franck: Symphony in D Minor, FWV 48 (Remastered)

The most brilliant of Belgian composer César Franck's compositions were written during the final decade of his life; the Symphonic Variations for piano and orchestra, the famous Violin Sonata, the D major String Quartet, and, perhaps most important, the Symphony in D minor are all the products of a single, remarkable five-year period. The Symphony, by no means an immediate success with critics or audiences, has nevertheless become so fused with the popular image of César Franck that it is nearly impossible to think of him without also thinking of this 40-minute orchestral juggernaut. And yet the work is by no means an empty audience-pleaser: as with all of his final compositions, the Symphony shows a superb synthesis of Franck's own uniquely rich harmonic language and cyclic themes with the traditions of Viennese Classicism that he had come to revere later in life (principally through the music of Beethoven).

Franck casts his Symphony in the still-rather unusual three-movement mold. A richly chromatic Lento introduction (almost agonizingly slow) presents the fundamental motivic unit of the first movement: a three-note dotted figure that moves down by semitone and then moves back up again by any either minor third or perfect fourth. The Allegro non troppo body of the movement takes off with a strident, fortissimo utterance of that same basic three note idea and its answer. An angry descending figure imitated at the half-bar, and a more searching, melodic idea round off the material, but Franck, refusing to be bound by tradition, cuts off the motion after just 20 bars to make another go at the introduction, this time a minor third higher (in F minor). Once again, the Allegro non troppo is achieved, and this time the body of the movement is allowed to work itself out. Over the course of the action, a new and triumphant melody (initially in F major) is introduced: this idea, sometimes known as the "faith" motif, will return in the Finale to powerful effect. The B flat minor second movement (Allegretto) displays characteristics of both slow movement and scherzo. The gentle, triple meter dance tune of the English horn (an instrument whose inclusion in a symphonic work was strongly objected to by the Parisian critics of the day) has something of the feel of a Medieval French ballad or dance. The gentle strumming of the harp and pizzicato strings gives way to a more searchingly chromatic consequent melodic strain, attired in attractive sixteenth notes. The middle (scherzo) section of the movement offers a delightful, contrasting dotted melody in E flat major. Throughout this movement, pauses in the rhythmic flow (indicated by fermatas) are used in a graceful manner. The Finale (Allegro non troppo) is altogether more exuberant in tone, beginning with bright wind attacks against a solid background of octave Ds in the strings. A sudden shift to pianissimo is made for the highly syncopated but still flowing main theme (cellos and bassoons, dolce cantabile). As this melody is taken through the characteristically Franckian chromatic depths, both the main theme of the Allegretto and the "faith" motif from the first movement (now offered a more tender treatment) return to fulfill the Symphony's cyclic element. On its second appearance in this movement, the Allegretto theme takes on a power and volume that one wouldn't think possible given its gentle contours during the middle movement. The happy opening melody returns to make a joyous end. (Blair Johnston, AMG)

NBC Symphony Orchestra

Guido Cantelli, conductor

Digitally remastered

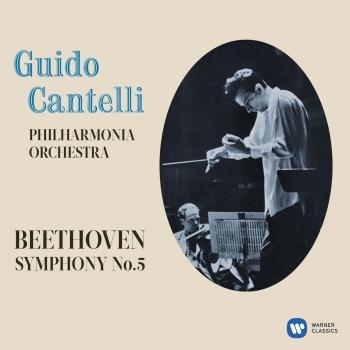

Guido Cantelli

Cantelli’s father was a bandmaster in the Italian army and as a boy Guido was a member of his father’s military band. He also played the organ in church, conducted a local choral society, and by the age of fourteen was giving piano recitals in public. At the Milan Conservatory he studied composition as well as conducting and made his first professional appearance as a conductor directing Verdi’s La traviata in Novara at the Teatro Coccia, which had been founded by Toscanini in 1899. During World War II he was initially a member of the Italian army, but for his refusal to fight on the side of Fascism he was imprisoned in a labour camp on the Baltic coast. He escaped using forged papers and eventually returned to Novara where he worked as a bank clerk, possibly under a false name.

With the end of the war he quickly resumed his interrupted conducting career, securing work with the orchestra of La Scala both in Milan and on tour. Both the music director and the intendant of La Scala, Victor de Sabata and Antonio Ghiringhelli, recognised his talent and supported him. Toscanini heard Cantelli for the first time in 1948, conducting the orchestra of La Scala in a rehearsal for a concert. He saw in him a reflection of what he took to have been his own conducting style at Cantelli’s age, and immediately invited him to conduct the NBC Symphony Orchestra in New York. Cantelli appeared with the orchestra for the first time during January 1949 and was recording with it a mere two months later.

With Toscanini’s active support and his obviously exceptional talents as a conductor, Cantelli immediately shot to the top of the conducting tree. He appeared in America every year up to his death, with the New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony and NBC Symphony Orchestras. Together with de Sabata he appeared with the La Scala Orchestra at the Edinburgh Festival in 1950, and shortly after took over from an indisposed de Sabata a concert with this orchestra in London. He was quickly signed up by Walter Legge to record with the Philharmonia Orchestra, and in 1951 started to make the first of many distinguished recordings for EMI. In addition to a busy schedule of concerts and recordings in America, Italy and Great Britain, Cantelli conducted at major festivals such as those of Lucerne and Salzburg. At the time of his unfortunate death in an aeroplane crash at Orly airport he had just been appointed as chief conductor at La Scala, following a scintillating production of Mozart’s Così fan tutte at the Piccola Scala, and was being actively considered as a successor to Dimitri Mitropoulos as the chief conductor of the New York Philharmonic.

Although in Cantelli’s conducting Toscanini saw himself as a young musician, Cantelli was musically too strong an individual to be simply a reflection of the maestro. Like Toscanini he emphasized fidelity to the score com’è scritto (as written) in terms of tempo and detail, and he had no time for the subjectivity that was common during his lifetime; however in addition Cantelli brought to his performances a sense of musical taste, a sensitivity of balance, and a tonal beauty that had been less emphasised by both Toscanini and Furtwängler in their own respective searches for textural fidelity and emotional truth. In this respect Cantelli was more a beginning than an end.

He was a meticulous and tireless rehearser. The New York Philharmonic Orchestra, typically tough, gave him little leeway until he stabbed his left palm with his baton during a rehearsal of Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler Symphony. The wound began to bleed but Cantelli carried on regardless until John Corigliano, the leader of the orchestra, jumped up to help the suddenly ailing maestro. Cantelli would not call off the rehearsal, and after his hand had been treated and bandaged, he continued. Only then did the orchestra give him its undivided and wholehearted attention. In his desire for perfection he could insist upon numerous takes in the recording studio of passages that the orchestra already knew well, and his frustration at not being able to achieve his ideal could result in occasional outbursts of anger. Yet as an individual he was modest and retiring.

His recorded legacy consists of many fine studio recordings and numerous ‘off-air’ recordings of studio performances and concert relays. For EMI he recorded with the Philharmonia Orchestra outstanding accounts of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, Brahms’s Symphonies Nos 1 and 3, Schumann’s Symphony No. 4 and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6, as well as atmospheric performances of music by Debussy and Ravel. He collaborated with the NBC Symphony Orchestra in fine accounts of Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler Symphony, Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition and Franck’s Symphony. Regrettably his only studio performance with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra was of Vivaldi’s Le quattro stagione. Of particular interest are the many recordings of broadcasts given by Cantelli with the NBC Symphony and New York Philharmonic Orchestras, which have been extensively reissued; as has an unofficial recording of Mozart’s Così fan tutte from Milan.

This album contains no booklet.