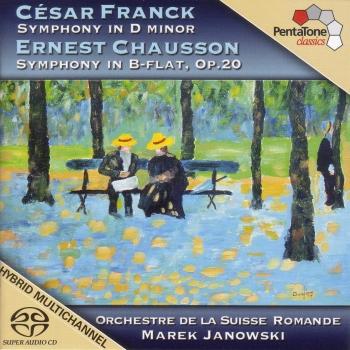

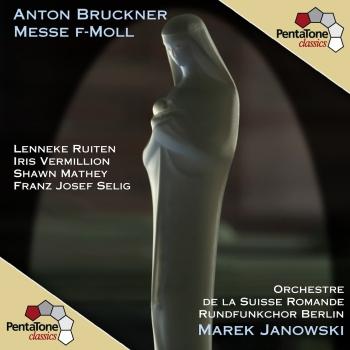

Symphony No. 4 in E Flat Major (The Romantic) 1878-80 version Orchestre de la Suisse Romande & Marek Janowski

Album info

Album-Release:

2013

HRA-Release:

25.12.2013

Label: PentaTone

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Artist: Orchestre de la Suisse Romande & Marek Janowski

Composer: Anton Bruckner (1824-1896)

Album including Album cover

- Anton Bruckner (1824-1896): Bruckner Symphony No. 4 in E-flat, WAB 104, Romantic

- 1 I. Bewegt, nicht zu schnell 18:15

- 2 II. Andante quasi allegretto 15:30

- 3 III. Scherzo: Bewegt 10:53

- 4 IV. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell 18:46

Info for Symphony No. 4 in E Flat Major (The Romantic) 1878-80 version

This is the last release in PentaTone’s Bruckner Symphonies cycle with the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande.

The Romantic (the title is Bruckner’s and is written on the manuscript), like his Symphony No. 3, follows the tradition of the sinfonia caratteristica. Famous models of this type of symphony are Beethoven’s Eroica and Pastorale, Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique, Mendelssohn’s Scottish and Italian, or the Dante and Faust symphonies by Liszt – works which were preferred by Bruckner (in contrast to the dogma of music esthetics, which is still today making efforts to hold up the banner of “absolute” music). Bruckner began his Fourth Symphony on January 2, 1874 and, considering his huge work load of teaching and organ playing, finished it quite quickly. The formidable score (1987 measures) was finished “at 9:30 in the evening” on November 22. In his letters, Bruckner wrote decisively of its subject matter: “In the Romantic fourth symphony, the first movement refers to the horn proclaiming day-break from the top of the town hall! Then daily life commences; the theme in the Gesangsperiode [“song period”, Bruckner’s term] is the ‘zizibe’ song of the Great Tit.” The model for the Funeral March (Bruckner: “Second movement: song, prayer, serenade”) whose muted strings create unique effects of distance, follows the March of the Pilgrims from Berlioz’ Harold in Italy Symphony as a model. In the first version, the rather quick movement only rarely has the constant prayer- like atmosphere of the slowed later version; occasionally it even recalls by contrast “Frère Jacques” in Mahler’s Symphony No. 1.

The elegant third movement is also composed in a naturalistic, virtually Schumannesque mood. With alternating responsorial singing of solo horn and tutti the atmosphere of the Andante carries on without interruption. This Scherzo is thematically better integrated than its successor, since its horn theme goes back to the wake-up call in the first movement, while the “Hunt Scherzo” inserted later (1878) only makes use of the familiar “Bruckner rhythm” of the first theme while introducing entirely new material. Little wonder, then, that Bruckner felt compelled to compose a new, rhythmically much tamer Finale in 1880, which was capable of incorporating the new main theme of the “Hunt Scherzo” at the beginning. This is not the least important reason why a breach seems to run through the conventional late version; the original version appears more cogent.

The score shows Bruckner making daring experiments which he himself hardly surpassed again. The sustained quintuplet rhythm of the Finale places great demands on the musicians, and some passages are playable only with difficulty, such as the syncopated oscillations in the violins in the final coda reminiscent of Debussy’s La Mer. The movement unleashes the rousing drive of a toccata – more daring than anything Bruckner was to write thereafter, until the unfinished Finale of his Ninth. He was stirred by a feverish Sturm-und- Drang mood and many passages are mere layers of sound which are only intended to be filled with motif work in later variants.

To prepare for this recording, the extant manuscripts were thoroughly examined, since the critical commentary to the first version of the Fourth Symphony had not

yet appeared in 2007. Of significance to its performance practice is also a letter written by Bruckner on December 6, 1876 to the Berlin critic Wilhelm Tappert, who had made efforts (albeit unsuccessfully) to have the work premiered in Berlin under Royal Music Director Benjamin Bilse. It includes a sheet of music to the Andante with Bruckner’s corrections, stating that, in the second theme, designated “Adagio”, the musicians should play “the quavers equivalent to the preceding crotchets”. This passage causes problems for those conductors in particular who are no longer aware that Bruckner categorically expected tempo relations to follow the Tactus Principle of Viennese classical music, and thus start off here in a new, wrong tempo. Unlike other conductors, Roger Norrington also keeps the transitions from the Scherzo to the Trio exactly as they are given in the score. Bruckner’s idea of tempo was quicker in the early version, where the first movement is marked “Allegro”, not “Allegro moderato” as in 1877. Neither the manuscript nor the copy indicates any tempo at all for the Finale. Nowak therefore added by inference the “(Allegro moderato)” from the later version, although the main tempo of the first movement is certainly supposed to be retained in the fourth movement, so the movement should actually be designated “Allegro” here.

For the planned Berlin performance, Bruckner made a number of corrections which he did not enter into his autograph, however, but into the first copy of it (Austrian National Library, Mus. Hs. 6032). Heretofore, scholars considered them to be a preliminary stage of the revision of 1878, and thus Nowak did not incorporate them into the critical edition of the first version. However, some of these corrections are markedly effective; Roger Norrington adopts a few of them in his performance – apart from a small number of corrections to minor details (notes, etc.), a kettle drum solo in the transition from the exposition to the development (bars 224–226) in the Finale, replacing a general rest of three bars. The violin solo in the first movement (bars 201–214) is sure to elicit surprise. Although not found in the sources, the passage nonetheless so well matches the character of other violin solos by Bruckner (Symphony No. 2, Andante; Symphony No. 8, Adagio and Finale; various works of church music) that Roger Norrington here decided to make use of this lovely coloring.

Roger Norrington began to support a historically informed performance practice in regard of Bruckner as early as the 1990’s. Fresh approaches of this nature make it easier to learn to hear anew such a radical score as the copy of the Fourth. Norrington’s spontaneous way of playing music, his youthful curiosity and delight may even perhaps tally particularly well with Bruckner’s own approach to the composition. (www.swrmusic.de, Benjamin Gunnar Cohrs)

Uppsala Chamber Orchestra

Marek Janowski, conductor

No biography found.

This album contains no booklet.