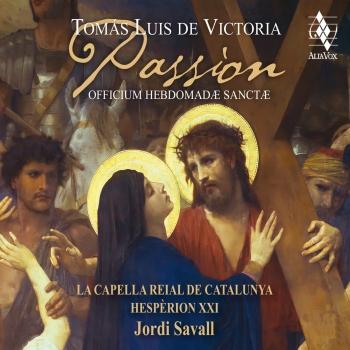

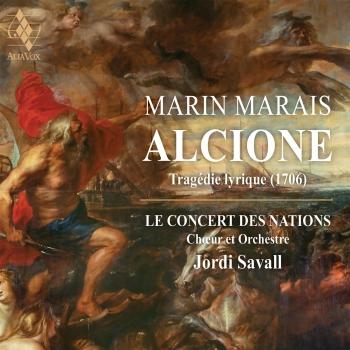

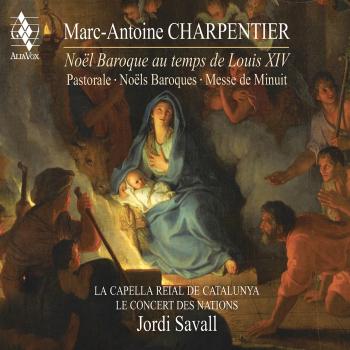

Marin Marais: Alcione Jordi Savall

Album info

Album-Release:

2021

HRA-Release:

24.09.2021

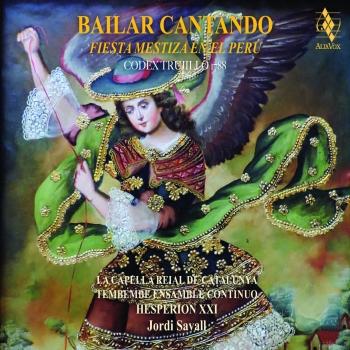

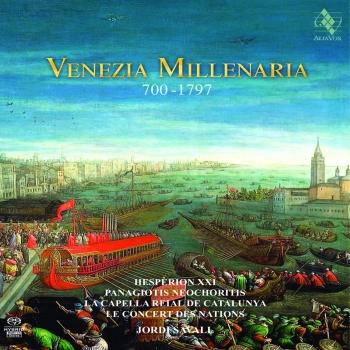

Label: Alia Vox

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Opera

Artist: Jordi Savall

Composer: Marin Marais (1656-1728)

Album including Album cover

- Marin Marais (1656 - 1728): Alcione, Prologue:

- 1 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: Ouverture 03:36

- 2 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: "Apollon et le Dieu des bois" 02:01

- 3 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: Air des Faunes et des Driades 02:25

- 4 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: "Fuyez, fuyez, mortels, fuyez" 02:08

- 5 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: Ritournelle: "Aimable paix, c’est toi que célèbrent mes chants!" 01:37

- 6 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: "Règne, règne, fille du ciel, mets la discorde aux fers" 03:06

- 7 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: Prélude - "A l’éclat de vos chants" 02:00

- 8 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: Marche (pour les Bergers et les Bergères) 01:31

- 9 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: 1er Menuet (pour les mêmes) - "Le doux Printemps ne paraît point sans Flore" 02:57

- 10 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: Bourrée (pour les mêmes) 00:46

- 11 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: Premier et deuxième Passepieds (pour les mêmes) 02:03

- 12 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: "Qu’un spectacle charmant signale ma victoire" 02:59

- 13 Marais: Alcione, Prologue: Entr’acte (Reprise de l’Ouverture) 03:28

- Alcione, Acte I:

- 14 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 1 : "Vous voyez le palais où l’hymen d’Alcione" 02:30

- 15 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 1 : "Trop malheureux Pelée, hélas ! Quelle est ta peine?" 00:54

- 16 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 1 : "J’oserai plus pour vous, seigneur, que vous n’osez" 01:12

- 17 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 2: "Aimez-vous sans alarmes" 02:23

- 18 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 2: "Partage, cher amie, les transports de mon âme" 00:50

- 19 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 2: "Du plus ardent amour mon cœur est enflammé" 01:13

- 20 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 2: "Ah ! Que ton cœur n’est-il plus tendre" 01:09

- 21 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 2: "Que rien ne trouble plus une flamme si belle" 01:02

- 22 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 2 : "Chantez, chantez, faites entendre" 01:16

- 23 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 2: "Que rien ne trouble plus une flamme si belle" (II) 01:56

- 24 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 2: Air gravement et piqué 01:45

- 25 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 2: Sarabande et deuxième air "Que vos désirs puissent toujours renaître!" 03:03

- 26 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 2: Gigue 01:00

- 27 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 2: Menuet - "Dans ces lieux, amour, tu nous ramènes" 02:05

- 28 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 3: "On approche : cessez, et qu’un profond silence" 00:50

- 29 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 3: "Le flambeau de l’amour n’a fait naître en votre âme" 00:53

- 30 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 3: "Écoutez nos serments, arbitres des humains" 00:57

- 31 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 3: Tempête - "Quel bruit ! Quels terribles éclats!" 01:18

- 32 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 3: "Ce n’est point mon palais qu’il faut réduire en poudre" 00:56

- 33 Marais: Alcione, Acte I Scène 3: "Quel embrasement ! Quel ravage!" 02:04

- Alcione, Acte II

- 34 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 1: Prélude - "Le Roi dans ces lieux va se rendre" 02:14

- 35 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 2: Prélude lentement - "Dieux cruels, punissez ma rage et mes murmures" 02:38

- 36 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 2: "L’injuste Ciel à mes maux m’abandonne" 03:13

- 37 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 2: "Vous, dont les mystères affreux" 01:40

- 38 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 3: "Éprouvez notre ardeur fidèle" 02:19

- 39 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 3: Premier Air des Magiciens 01:05

- 40 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 3: "Sévère fille de Cérès" 02:10

- 41 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 3: Symphonie - "Fleuves affreux qui, par vos noirs torrents" 02:38

- 42 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 3: Premier Air des Magiciens - "Nos vœux sont écoutés dans les royaumes sombres" 02:54

- 43 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 3: Deuxième Air des Magiciens 01:09

- 44 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 3: Symphonie - "Une fureur soudaine a saisi mes esprits" 01:16

- 45 Marais: Alcione, Acte II Scène 3: "Qu’entends-je ! Quel funeste oracle!" - Deuxième Air des Magiciens 02:25

- Alcione, Acte III:

- 46 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 1: Prélude - "Ô Mer, dont le calme infidèle" 04:10

- 47 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 2: Prélude gay - "L’amour vient de vous faire une faveur nouvelle" 01:16

- 48 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 3: Marche - "Contraignez-vous, on vient" 00:29

- 49 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 3: Marche pour les Matelots et Matelotes 00:52

- 50 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 3: "Régnez, Zéphirs, régnez sur la liquide plaine" 03:22

- 51 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 3: Marche pour les Matelots et Matelotes - "Amants malheureux" 01:42

- 52 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 3: Deuxième Air des Matelots et Matelotes - "Pourquoi craignons-nous" 02:00

- 53 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 3: Troisième Air des Matelots et Matelotes 01:07

- 54 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 4: Ritournelle violons - "Quoi, les soupirs et les pleurs d’Alcione" 02:35

- 55 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 4: "C’est toi que j’en atteste" 04:59

- 56 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 5: "Il fuit… Il craint mes pleurs" 01:46

- 57 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 5: "Que vois-je ? De ses sens elle a perdu l’usage" 02:32

- 58 Marais: Alcione, Acte III Scène 5: Marche pour les Matelots et Matelotes 01:35

- Alcione, Acte IV:

- 59 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 1: Ritournelle violons - "Amour, cruel Amour, sois touché de mes peines" 03:42

- 60 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 2: Violons - "On prépare le sacrifice" 04:50

- 61 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 3: Prélude - "Ô Toi, qui de l’Hymen défends les sacrés nœuds" 02:02

- 62 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 3: Sarabande 00:57

- 63 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 3: "Dieu des amants, heureux qui sent tes flammes" 01:00

- 64 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 3: "Reine des Dieux, exauce nos souhaits" 01:58

- 65 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 3: Flûtes (on entend une Symphonie fort douce) 00:58

- 66 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 3: Symphonie violons et flûtes allemandes - "Quels sons charmants!" 02:30

- 67 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 3: Symphonie - "Eloignez-vous et laissez Alcione" 02:21

- 68 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 4: "Volez, Songes, volez, faites-lui voir l’orage" 01:26

- 69 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 5: Tempête 01:27

- 70 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 5: "Ciel ! Ô Ciel, quel affreux Orage!" 01:53

- 71 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 6: "Où suis-je et qu’ai-je vu ! Je perds ce que j’adore" 03:34

- 72 Marais: Alcione, Acte IV Scène 6: Menuet Entr’acte 01:13

- Alcione, Acte V:

- 73 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 1: Prélude - "Ô nuit ! Redouble des ténèbres" 02:55

- 74 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 1: "Qu’ai-je fait, malheureux!" 00:41

- 75 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 2: Ritournelle (flûtes) 01:32

- 76 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 2: "Barbares, laissez-moi ; votre pitié m’offense" 01:28

- 77 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 2: "Ombre de mon époux, c’est par toi que je jure" 03:27

- 78 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 3: Ritournelle (flûtes) - "Quel Dieu descend ici ? Quel Astre nous éclaire?" 01:41

- 79 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 4: "Qu’ai-je entendu ? Grands Dieux : croirai-je cet oracle?" 01:25

- 80 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 5: "Régnez, Aurore, à votre tour" 02:07

- 81 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 5: "Mais, quel funeste objet a frappé mes regards!" 03:16

- 82 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 6: Prélude - "Je viens vous affranchir de la Parque cruelle" 03:02

- 83 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 6: "Quoi ! Je revois Ceix" 00:53

- 84 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 6: "Chantez, divinités de l’onde" 01:56

- 85 Marais: Alcione, Acte V Scène 6: Chaconne 06:46

Info for Marin Marais: Alcione

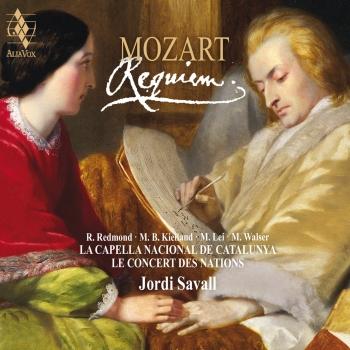

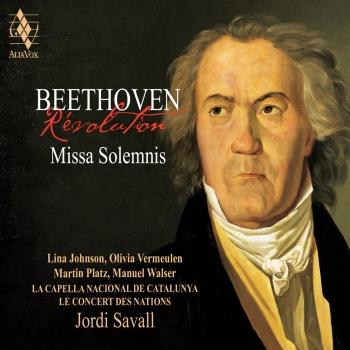

The last great tragédie en musique or “musical tragedy” of the reign of Louis XIV, Alcyone (Alcione, as the title appears in the 1706 edition) is an all-round spectacle poised between the 17th and 18th centuries. From the 17th century it takes its mythological source, its prologue in praise of the king, its high literary quality and its vocation for spectacle, combining choreography and changes of scenery. In the depth of the emotions experienced by its protagonists, more sensitive than heroic, as well as in the expressiveness of the orchestra which envelopes them in a true sound décor, it ushers in the 18th century.

Structured, like all musical tragedies, in the form of a prologue and five acts, Alcyone was conceived by a successful young librettist, Antoine Houdar de La Motte, and Marin Marais, the most famous violist of his day. The magnificent portrait of Marais by André Bouys was widely distributed at the time in the form of an engraving. At about the age of fifty, Marais had just been appointed to the prestigious position of batteur de mesure (in modern terms, conductor of the orchestra) of the Royal Academy of Music at the Paris Opéra. Alcyone’s premiere on 18th February, 1706, was a major event, both for the composer and for the institution itself, which since 1673 had been installed in the Théàtre du Palais-Royal, at that time the residence of the Duke of Orléans, in what is now the Conseil d’État or Constitutional Council, and which was roughly the same size as the present-day Salle Favart, home to the Théâtre National de l’Opéra Comique.

In 1706, 19 years had passed since the death of the former director of the Opéra, Jean-Baptiste Lully, and the institution found itself in a fragile state. At Versailles, pleasure had long since been ousted by piety. Under the influence of Madame de Maintenon and Bossuet, the monarch was reconciled to Rome before dragging France into the long War of the Spanish Succession. New operas were very rarely staged at court, and they were not necessarily performed in the presence of the king. The fragile financial health of the realm’s foremost public theatre led the Opéra’s privilege-holders to put management in the hands of contract employees: a director and a number of sponsors. The repertory was opened up to Lully’s successors and embraced new lyrical formulas. The opéra-ballet, an entertaining genre represented by the works of Colasse and Campra, had for ten years enjoyed a roaring success.

Louis XIV did not attend the first performance of Alcyone, of which the prologue, as was de rigueur in this official genre, nevertheless extolled his might. Following the custom of the previous fifty years, the king is represented in the guise of Apollo, who triumphs over Pan by singing a hymn to peace: “Amiable Peace, […] / Happy, happy the victor who takes up arms / Only to restore you to the world.” Apollo then orders “a fine pageant” to mark his victory and instructs the muses to repeat the story of the Halcyons, the divinities who watch over the calm of the oceans, which was so vital to the prosperity of the French navy!

The following five acts tell in five tableaux the story of the Halcyons, or rather that of their parents, as taken from Book XI of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the source of numerous operatic subjects of the period. It revolves around Ceyx, King of Trachis in Thessaly and the son of Phosphorus, the god of light, and Alcyone, the daughter of Aeolus, the god of the winds. Like Alceste, Armide, Dido and many others, the heroine gives her name to the opera, guiding the spectators through a labyrinth of passions which are less political and more intimate in nature than masculine passions. The daughter of a god who rules the elements, she anchors the work in the marine environment, a judicious choice for a show which, in the Baroque period, owed its spectacular qualities (scenic carpentry, stage machinery, set-change mechanisms) to naval engineers and technicians.

The heterogeneous audiences at the Opéra were less reticent than royalty when it came to being won over, from the very first evening, by Jean Bérain’s sets and the remarkable performance conducted by the composer himself. The finest singers and dancers of the company graced the stage, and in the orchestra pit, brightly lit like the rest of the theatre, sat the finest orchestra in Europe. It brought together some forty musicians, most of whom were reputed soloists and even composers in their own right. Inventive, colourful and varied, Marais’s score was all the enthusiastically received in that it included an already popular character from opera, Peleus, the friend and unhappy rival of Ceyx, and at least one folk tune transformed into the sailors’ chorus in Act III. When Alcyone was performed, box- office takings were almost 60% higher than on other evenings.

The revivals of Alcyone at the Opéra bear witness to its enduring popularity, despite the fact that the nature of musical spectacles at that time was undergoing a shift toward dance, variety and entertainment. The 1719, 1730, 1741, 1756, 1757 and 1771 revivals of the work suffered changes and cuts, the brunt of which were borne by the prologue, but the sea storm and, above all, the tempest, remained a must. The storm was included in a revival of Lully’s Alceste in 1707, quoted by Campra in Les Fêtes vénitiennes in 1710… Proof of its huge popularity were the parodies accompanying a number of revivals: Fuzelier wrote L’Ami à la mode ou parodie d’Alcyone in 1719 for the actors and marionnettes of the Foire Saint-Germain, and in 1741 Romagnesi composed a parodic Alcyone for the Théâtre-Italien.

If the storm scene enjoyed particular success, it was because of its ability to depict unbridled nature by “concealing art with art”, something for which Jean-Philippe Rameau also strove – in other words, by using all the resources of serious music to translate the chaos of the elements. With his descriptive symphony, Marais promoted a new vision of his art: henceforth, not only would music be able to portray everything, but it would pull no punches to achieve that goal, incorporating new instruments as well as new ways of playing them. The doors opened to musicians by Marais would never again be closed.

It is this creative freedom and this art of enchantment that is brought to life by Jordi Savall as director of the Concert des Nations, playing on period instruments, and Louise Moaty, assisted by Raphaëlle Boitel, in the first Paris stage production of Alcyone since 1771.

Antonio Abete, bass

Lisandro Abadie, bass

Cyril Auvity, tenor

Lea Desandre, mezzo-soprano

Marc Mauillon, baritone

Le Concert des Nations

Jordi Savall, conductor

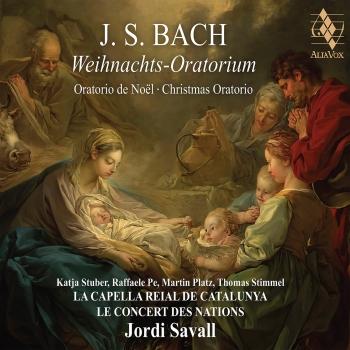

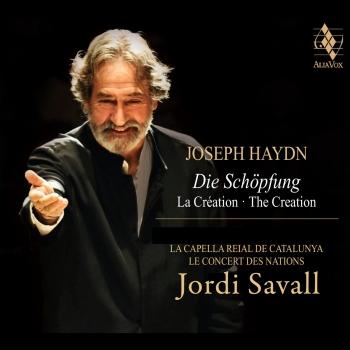

Jordi Savall

Born on August 1, 1941, in Igualada, near Barcelona, Spain; married Montserrat Figueras (a musician), 1968. Education: Barcelona Conservatory, diploma; Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, diploma, 1970. Addresses: Record company---Naive Classique, 148 rue du Faubourg Possinière, 75010 Paris, France.

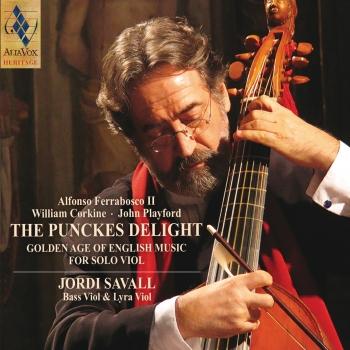

The works performed by Catalan gambist and conductor Jordi Savall span several centuries---from the music of Alfonso el Sabio, king of Castile and Léon, to the works of J. S. Bach---bringing to life the splendor and passion of bygone eras. A performance by Savall is more than a musical experience: the extraordinary power and beauty of his playing magically removes the listener from the flux of time, creating a space in which such obstacles to enjoyment as historical distance, stylistic peculiarities, and idiomatic enigmas simply disappear. For example, historical periods, including the Baroque, have often been described as "distant." Indeed, the physical and mental universe of seventeenth-century France may seem distant to a person living in the twenty-first century. But that distance vanishes when Savall plays the music of the great French master of the bass viol, Marin Marais.

First of all, Savall's main instrument is the viola da gamba, or bass viol (he also plays the smaller viols), not as a quaint relic that needs some special justification or antiquarian explanation. True, in the late 1700s, the viola da gamba---which is not a different kind of cello, but a member of the viol family, a distinct group of instruments of varying sizes---was supplanted by the cello, as the latter instrument, with its potential for virtuosity, satisfied the requirements of changing musical styles. However, to Savall, his instrument is irreplaceable. In fact, according to Savall, the viola da gamba has a particular sonic richness that the more "modern" cello lacks. As Savall explained to Chris Pasles of the Los Angeles Times, the "viola da gamba is totally different from a cello. It's closer to the lute---a lute with a bow, in fact. With six strings, frets like a guitar, a softer sound, it's more rich in different colors." Instead of merely reproducing a particular musical composition, Savall captures and expresses the timeless humanity of the music, illuminating the particular composition as a universally comprehensible document of the human experience. A case in point is Savall's mesmerizing performance of Marais's musical description, found in Book V of his Pièces de viole, of his gallstone operation. Written under the influence of François Couperin's character pieces, this extraordinary composition, especially in Savall's version, remains one of the most suggestively dramatic works of Baroque music.

Born in 1941, near the Catalan city of Barcelona, Savall began his musical education at the age of six. After graduation from the Barcelona Conservatory, where he studied the cello, Savall went to Basel, Switzerland, where he studied the viola da gamba with August Wenzinger at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, receiving a diploma in 1970. His other teachers included Wieland Kuijken, in Brussels. In 1973 Savall took over Wenzinger's post at the Schola Cantorum. By the early 1970s, Savall was already considered one the greatest viola da gamba players. In addition, he worked hard to enrich his instrument's repertoire, rescuing many works from oblivion and performing and recording numerous forgotten compositions. Savall thus exemplified, as he still does, the learned performer, who constantly studies the vast field of old music, bringing many neglected compositions to light. Among these lesser-known compositions are works by Marais, whose rich and fascinating oeuvre includes more than 500 pieces for viola da gamba and keyboard accompaniment, assembled in five books of his Pièces de viole.

In 1974 Savall and his wife, soprano Montserrat Figueras, founded Hespèrion XX---later, in the twenty-first century, known as Hespèrion XXI---an international ensemble that has gained great acclaim for its extraordinary performances of music from the Middle Ages to the Baroque. In 1987, returning to his native city after his extensive sojourn in foreign lands, Savall formed the Capella Reial de Catalunya, a vocal group that, under his direction, has performed and recorded music by Tomáa Luis de Victoria, Francisco Guerrero, and Claudio Monteverdi.

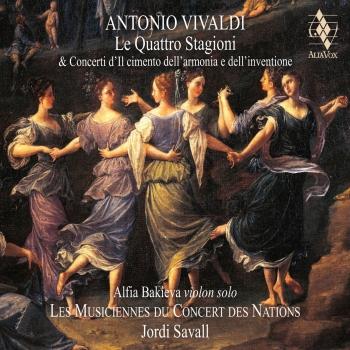

In 1989, further expanding his repertoire and musical activities, Savall founded the Concert des Nations, an ensemble consisting of younger musicians from Spain and Latin America. Under Savall's direction, this orchestra, which plays on period instruments, has recorded a variety of works from the Baroque and Classical periods.

Savall's career received a tremendous boost when film director Alain Corneau asked him to play on the soundtrack for Tous les matins du monde, his 1992 film about Marais and his teacher, Sainte-Colombe. Based on Pascal Quignard's admirable 1991 novel--available in English as All the World's Mornings--which imagines the life of the mysterious Sieur de Sainte-Colombe, the film is a spell-binding portrait of seventeenth-century France with the music, performed by Savall, providing a foundation for the narrative. Savall himself indirectly inspired Quignard's novel: it was a 1976 recording by Savall that introduced the writer to Sainte-Colombe's music. The music that Savall performs on the soundtrack is mostly by Marais and Sainte-Colombe, though it also includes a segment of François Couperin's deeply spiritual Leçons des ténèbres. Savall is inspired in his performance of the heartrending Tombeau les regrets, which, in Quignard's imagination, Sainte-Colombe played to conjure up the spirit of his deceased wife. In Savall's hands, this music, which appears as a leitmotif throughout the film, graces the rich tapestry of the film as a mysterious aura.

In 1988 the French Ministry of Culture awarded Savall the title of Officier de l'Ordre des Arts et Lettres. His recordings, numbering more than one hundred, have received many awards, including the Double Disc of Gold and the Diapason d'Or. In 1997 Savall's recording company, Astrée, founded a separate label, Fontalis, for his recordings. The following year, Savall started his own label, Alia Vox, which later reissued many of his earlier recordings at an affordable price. Savall's remarkable career is more than a personal triumph: thanks to his superb musicianship, the viola de gamba has emerged from the shadows of the past, becoming the instrument of choice for many younger performers. For such performers, the rich repertoire of the Renaissance and Baroque offers not only infinite artistic challenges and possibilities but the opportunity to abolish the somewhat artificial barrier separating "early" music from the rest of the musical tradition. (Zoran Minderovic)

This album contains no booklet.